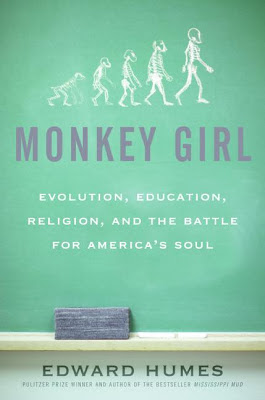

Monkey Girl:

Evolution, Education, Religion,

and the Battle for America's Soul

by Edward Humes

(Harper Perennial)

Of Pandas and People:

The Central Question

of Biological Origins

by Percival Davis and Dean H. Kenyon

(Foundation for Thought and Ethics)

There are those who believe the universe is too irreducibly complex to be the result of random processes, such as natural selection and evolution. They are called intelligent design proponents. A devout colleague of mine suggests they aren't all religious, but the only example I can find is Bradley Monton, author of Seeking God in Science: An Atheist Defends Intelligent Design (Broadview Press). (Philosopher Jerry Fodor and cognitive scientist Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, authors of another often-cited book by intelligent design proponents, What Darwin Got Wrong, do not discuss intelligent design per se, only their problems with Darwinian evolutionary theory.)

My own views on the subject are based upon the research and interviews I did for a Macomb Daily article on the 2005 Dover, Penn., school board case (if you're wondering why a Michigan journalist wrote about a Pennysylania lawsuit, it was because Ann Arbor's Thomas More Law Center was the school board’s counsel), as well as the November 2007 Public Broadcasting Service NOVA television documentary “Judgment

Day: Intelligent Design on Trial,” and the book Monkey Girl.

(I haven't read Of Pandas and People, but since it plays such a large part in the case I've listed it as well. It's now out-of-print, but has been supplanted by the same publisher's The Design of Life: Discovering Signs of Intelligence in Biological Systems by William A. Dembski and Jonathan Wells.)

Basically, the lawsuit was about whether intelligent design was creationism, because the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled creationism as religion, and thus barred from teaching in public schools. (In Dover, a statement about intelligent design being an alternative theory to Darwin's theory of evolution was required to be read before the class, and that copies of the intelligent design text book Of Pandas and People were in the school library.)

Creationism states that the world was created by God as it says in the Bible, and that consequently the Earth is less than 10 thousand years old. Intelligent design states that the universe is too complex to be created by random forces and therefore must have had an intelligent designer (maybe God), but makes no claim as to the age of the Earth.

The problem from the scientist's view is that there seems no way to test whether or not there is a designer. It can be argued or deduced, but not shown. Many scientists also see “intelligent designer” as code for “God.”

The Thomas More Law Center had wanted a test case for intelligent design that could be taken all the way to the Supreme Court, but were thwarted when the district voters replaced all of the board members (at least all of the ones up for re-election that year) who supported the intelligent design statement before the verdict was reached. When the judge ruled against the old board, the case died there since the new school board wasn't interested in litigating the case.

My biggest problem with intelligent design or creationism is: so what? Aside from its religious agenda -- There is a God -- how does it help us understand the universe? Is the intelligent designer still making things happen, making cells reproduce, making the Earth rotate and circle the sun? If so, there's no need to study anything. We just all need to pray. If, however, we live in a world of physical laws, where agriculture is needed to make things grow, engineering and maintenance are necessary to keep machines running and water drinkable, human thought and effort are necessary to create new and better products and devices, then science is necessary. Intelligent design is not, except in the same sense as religion and philosophy.

In Dover, at least some of the opponents of intelligent design in the school were religious, were devout, but didn't want religion intruding into science. In Matthew 20:20-22, Jesus said, “Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar's; and unto God the things that are God's.” I feel public school boards should keep religion out of the science classroom. If you want to convince me that intelligent design isn't religion, I need more than one atheist's opinion to convince me, and at least one theory about who is this designer if he isn't God.

My original article, slightly edited from draft, is reprinted below.

By Stephen Bitsoli

Macomb Daily Staff Writer

In 1925, a Dayton, Tenn. high school substitute science

teacher named John T. Scopes was put on trial for the crime of teaching

evolution. Although Scopes lost the case (he was fined $100, with the

conviction overturned on a technicality on appeal), the anti-evolution movement

was given a black eye.

In 1987, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a Louisiana law

mandating the teaching of creationism (basically the biblical story of the

creation of the Earth and Man) in science classes, on the grounds that it

wasn't science and “advances a religious doctrine” in violation of

the Establishment Clause of the Constitution.

Now evolution is in the courts again, this time in Dover,

Pennsylvania, facing off against another alternate theory of human development

known by its proponents as intelligent design. Its critics call it

“creationism in a white coat.”

Kitzmiller et al. v. Dover Area School District is a case in

which eight families are challenging a school board decision that before

evolution can be taught, the instructor must read a one-minute statement that

says evolution has gaps that some believe can only be explained by

“intelligent design,” and informing them that a book in the school

library will explain the concept if they want to read it.

The American Civil Liberties Union is plaintiff counsel,

while the Ann Arbor-based Thomas More Law Center is defendant's counsel. The

ACLU claims that intelligent design is religion masked as science, and is in

fact just creationism under another name. Creationism, the belief that the

Bible's explanation of human (and earthly) origin is literally true, has been

ruled religion by the U.S. Supreme Court, and hence illegal to be taught in

American public schools. Proponents and the Thomas More Law Center claim that

intelligent design isn't creationism, isn't religion, and the school board

wasn't “teaching” it by requiring that a one-minute statement be

read.

Richard Thompson is chief counsel for Thomas More Law Center, but he

said he wasn't the lead counsel in the Dover case, just one of three. The

others are Patrick Gillen and Rob Muise.

“The case was concluded (Nov. 4).” Following three

weeks during which both sides can file pleadings, the judge will begin

deliberations. A verdict is expected before January.

By that time, eight of the nine members of the Dover School

Board will be out of office. They were defeated for reelection by a slate of

Democrats who vowed to reverse the intelligent design decision (though voters

may have been unhappy at the publicity and the cost of litigation too).

It was unclear at press time if the election results will affect the

expected appeals. Before the election, Thompson told The Macomb Daily that

regardless of which side prevails, appeals up to the U.S. Supreme Court were

almost certain.

Thompson insists that intelligent design isn't “creationism in a white coat” but a competing and perhaps

complementary “scientific theory.”

“Creationism,” Thompson said, “starts with

creation stories within Genesis and uses them as a basis.” From the Bible creationists deduce that the

Earth (if not the universe) is only between six and 10 thousand years old, not

four-and-a-half billion.

Intelligent design, Thompson said “doesn't address the

age of the Earth,” and “It doesn't deny there has been change over

time” in living organisms. “(ID proponents) look at empirical data

and come to a different scientific conclusion” than evolutionists, Thompson

said, namely that life is “irreducibly complex” and couldn't happen

by accident or natural selection. He repeated the example given by Michael

Behe, “a Roman Catholic microbiology professor” who testified at the

Dover trial, of “bacterial flagellum,” which has a “fully

functioning motor with 40 moving parts ... all of which had to be in place to

have any value.”

Thompson has also insisted that intelligent design isn't

religion. Yet on the Thomas More Law Center Web site, it

states that its raison d'etre is to defend religion: “The Thomas More Law Center is a not-for-profit public

interest law firm dedicated to the defense and promotion of the religious

freedom of Christians, time-honored family values, and the sanctity of human life.

Our purpose is to be the sword and shield for people of faith, providing legal

representation without charge to defend and protect Christians and their

religious beliefs in the public square.”

After the Nov. 8 election, another religious observer, televangelist

Pat Robertson, denounced the citizens of Dover for ousting the school board for

religious, not scientific reasons. According to the Reuters news service,

Robertson said, “If there is a disaster in your area, don't turn to God.

You just rejected him from your city.” Intelligent design seems, at the

very least, to have a strong religious component.

“Regardless of what happens (in the Dover case),”

Thompson said, “the genie is out of the bottle. You're going to see

intelligent design popping up all over the country.”

Thompson acknowledged that one board member in Dover had

wanted to add creationism to the curriculum, until informed that the U.S,

Supreme Court ruling precluded it. When some Dover residents contacted Thomas

More about other ways of balancing evolution, Thompson said, “we told them

about intelligent design.”

Kary Moss, executive director of the ACLU of Michigan, said

flatly that “Intelligent design is another word for creationism,”

period, and that the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that you can't mandate

creationism be taught in public schools. “I don't think it even has a

scientific veneer. The agenda behind this is the teaching of religion in public

schools.”

She referred to testimony that suggested the author of Of Pandas and People, the intelligent design book in the Dover

School libraries, originally used the term “creationism” and later

substituted the term “intelligent design.” (In the original manuscript, there was at least one example of sloppy search-and-replace of creationists with design proponents: it read cdesign proponentsists.) “They're just not happy with (the U.S.

Supreme Court decision).”

Paul Drummond, a science consultant for the Macomb

Intermediate school District, president elect of the Michigan Science Teachers

Association and executive director of the Metro Detroit Science Teachers

Association, said “I don't consider (intelligent design) a science.”

More, he said, “it's not a theory. A theory is not just an opinion. It's

much more rigorous.”

He quoted a statement from the National Academy of Sciences

which states that a theory “is a well-substantiated explanation of some

aspect of the natural world that incorporates tested hypotheses, laws, facts

and inferences.”

Intelligent design, as Drummond understands it, holds that “there are some things that exist in nature,” such as the human body

or a leaf, so complex “that suggest there is an intelligent design”

behind them, an intelligent designer.

Drummond said that “science is one way of knowing

things,” but not the only way. “It doesn't have a market on

truth,” but it is different from philosophy or theology, which Drummond

said is the proper place for intelligent design. “Science looks at what is

the evidence, what is testable.”

By contrast, questions such as “ ‘Is there a God?’ or ‘(is there) life after death?’ are outside the purview of science,”

Drummond said, and are properly the purview of philosophy or theology.

The reason intelligent design isn't science, Drummond said,

is because “it doesn't lead us to anything that could test the existence

of a designer.”

Intelligent design proponents, such as Michael Behe, instead

find holes or gaps in evolutionary theory, even propose tests for how you could

test evolution (one suggestion: study 10,000 generations -- about two-years’

worth -- of a bacterium and see if it produces a variation or mutation as

complex as the motor-like bacteria flagellum) without testing them themselves.

Behe's own fellow faculty at Lehigh University issued a

statement that “the (Department of Biological Sciences) faculty are

unequivocal in their support of evolutionary theory ... . It is our collective

position that intelligent design has no basis in science, has not been tested

experimentally, and should not be regarded as scientific,” while noting

that “The sole dissenter from this position (is) Prof. Michael Behe.”

Intelligent design proponents, Drummond said, claim there is

a debate in the scientific community about evolution, but “There is little or no debate on whether evolution

has taken place,” only the mechanism.

RSS

RSS